Janet Wilson is a regular opinion contributor and a freelance journalist who has also worked in communications, including with the National Party.

OPINION: You’re a first-term government elected on a mandate that you’ll lift the country’s Third World economy. Except for various reasons – your own inability to rein in spending, geopolitics, to name a couple – you don’t.

Now, mid-term, with voters giving you the thumbs down in a series of polls, what do you do?

Why, you find another form of government that the electorate arguably loathes even more and go to war with them. You threaten to abolish regional councils and, hypocritically, plan to cap rates while announcing new resource management powers giving central government the right to overrule councils if their decisions negatively impact economic growth, development, or employment.

Meanwhile, the country’s 78 councils make themselves easy to hate as they continue piling on annual rate rises to pay for their vanity projects and bad business decisions.

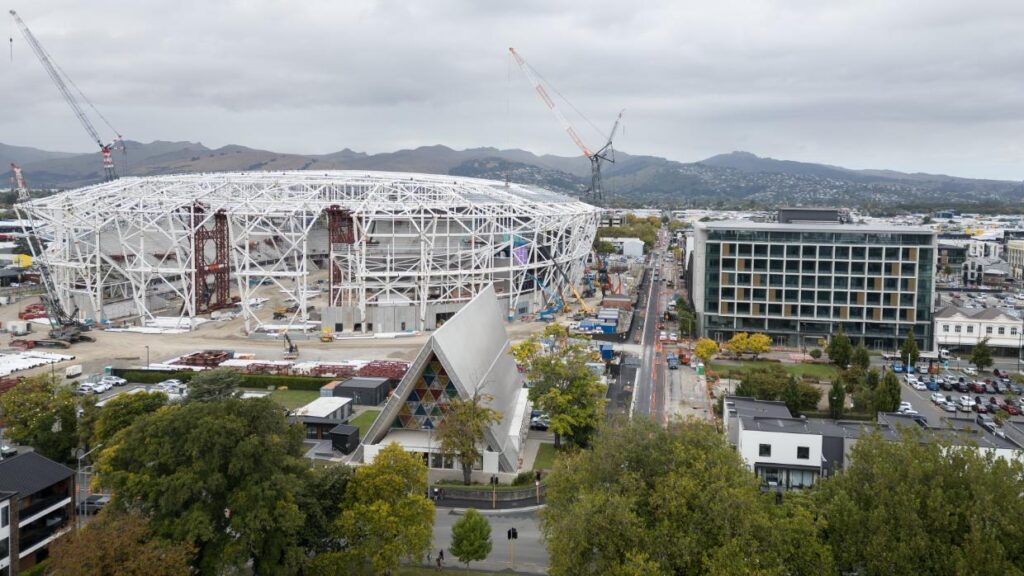

There’s Christchurch’s state of the art Te Kaha stadium, originally costed at $553 million but now estimated to cost $683m. Or Wellington’s $2.3m toilet complete with its own light show. Or the $1m Hastings District Council paid for an inner city building which it subsequently sold to a developer for $150,000, taking the notion of socialising the debt and privatising the rewards to a whole new realm.

Unsurprisingly, those three councils were among 18 New Zealand local authorities ratings agency S&P Global downgraded in March. The reason? A primary one was growing credit risk because the “predictability of central government policy settings on local councils is extremely volatile at the moment”, an S&P analyst said.

Councils are getting around 10% of their budgets from Crown grants when in other countries it’s more like 15-20% or more. Or, as the S&P analyst says, “you’re told to do more infrastructure spending, and you’re getting less support”.

This is the opposite of localism and resetting the relationship between central and local government that Christopher Luxon and National campaigned on two years ago. Instead, giving the housing minister the power to override democratically elected council decisions, even if it’s an interim measure ahead of new RMA laws, smacks of subverting the democratic process.

And it’s those changes to the Resource Management Act that the coalition Government is itching to get completed because it presents a compelling reason to get rid of the country’s 11 regional councils.

National has long seen them as a bureaucratic double-up and wanted them gone. Thirty-five years ago, it wound back regional council powers, leaving them ineffective and in a regulatory vacuum. What’s more, the public doesn’t understand why they exist, when local councils seem to do much the same work, which will exacerbate their demise even faster.

But it’s when it comes to the prospect of rates capping that National is at its sanctimonious worst. It may have got away with demanding more infrastructure from councils while cancelling Crown grant programmes, but the prospect of freezing rates is mean and penny-pinching.

It won’t work, Local Government New Zealand says, citing the rate-capping that has existed in the Australian states of Victoria and New South Wales for some time. Instead, it’s just going to exacerbate the infrastructure deficit hole the country already finds itself in, while cutting services and increasing debt.

But if there are misgivings from taxpayers about the direction the coalition Government is taking, it’s a clear second to the disenchantment ratepayers are feeling – and the taxpayer and ratepayer are usually the same person.

In a recent The Post/Freshwater Strategy poll, on the question of whether councils were providing value for money, a measly 27% agreed, while 41% disagreed. Nearly two-thirds, 63%, said they were concerned about the long-term sustainability of their council finances.

That amount of dissatisfaction sitting in communities across the motu doesn’t bode well for councillors, considering voting for local elections begins in September.

When it comes to the democratic process, the coalition Government has important leverage over their local body rivals – voter turnout.

In the 2022 local body elections only 42% voted, while a year later, in the general election, voter turnout was 77.5%, giving central government at least the argument that it has a mandate to do what it likes.

So despite serious misgivings, rates-capping will be introduced as an entrée to even more seismic changes for local bodies, the introduction of new laws to replace the RMA in October.

Is the end nigh for regional councils? Absolutely.

The end may be near, too, for other smaller councils with the possibility of further amalgamations on the table. A reality that LGNZ already recognises and is discussing further this month at its annual general meeting.

So much for Luxon’s assertion that “centralism over localism doesn’t work” as he told Parliament last year. That mantra applies only, it seems, when locals agree with him.

No doubt that is also why Luxon is forcing the 35 councils who introduced Māori wards in 2022 to hold a referendum to keep them.

And why councils who continue to keep doing “dumb stuff” will have the coalition Government’s form of “localism” imposed on them, Luxon style.